Oct 16

With 'Pru Payne,' Playwright Steven Drukman Examines America's Cultural Amnesia

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 7 MIN.

"High Art requires virtuosity," Prudence Payne – Pru for short – declares at the onset of Steven Drukman's play "Pru Payne," named for its titular character. "Proustian prose. Paderewski's piano. The plays of Pinter, the poetry of Pushkin – all of them: The apogee of rigor."

Taking aim at art designed to shock, as well as all the ways in which culture has become a matter of soundbites and political rivalries, Pru adds: "Befouling your naked body with dog doo in some downtown venue, well – not so much. Oh, we may feel your pain; what we fail to see is craft. 'You're here and you're queer?' Catchy – but it ain't Proust."

Drukman – an associate professor at New York University, whose inaugural play, "Going Native," premiered in 2002 and starred Billy Porter – is a former actor himself. His next play, "Another Fine Mess," produced the following year, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. A native of New England, he's set "Pru Payne" in the Boston area, and its to that same locale that the play is headed in an East Coast premiere production by the SpeakEasy Stage Company. The play received a workshop at the Merrimack Repertory Theater in 2018. A second reading took place the following year with Boston actress Karen MacDonald in the titular role. She stars in the SpeakEasy production, directed by Paul Daigneault. After several more drafts, the play premiered last year at the Arizona Theatre Company.

Highly educated, highly accomplished, erudite, and a little snappish, Pru was created by Drukman as a response to America's cultural amnesia (if not outright senescence), which hit a tipping point in 2016 (that year's election inspire Drukman to write the play) and has only worsened since.

Pru is a woman who's lived a full and rewarding life, but now – even as she's set to receive a prestigious award – it's all falling away with the onset of dementia. But even as her longtime persona begins to fade, another, more vibrant, version of Pru emerges, just in time for her to meet another older person – Gus, a working guy – and fall in love. They may seem a mismatch, but they invigorate each other so much that their doctor wants to keep them together in a facility for the sheer therapeutic value of their affair.

Pru's gay son, Thomas, once attended the tony prep school where Gus still works as a custodian. Gus' own son, Art, is closeted and was once a classmate of Thomas' – a classmate, and something more. Even as Pru and Gus experience a late-in-life blossoming, their sons rediscover each other, and passion ignites anew between them.

For more about the play, Steven Drukman's cultural observations, and his thoughts on the importance of queer representation, read on.

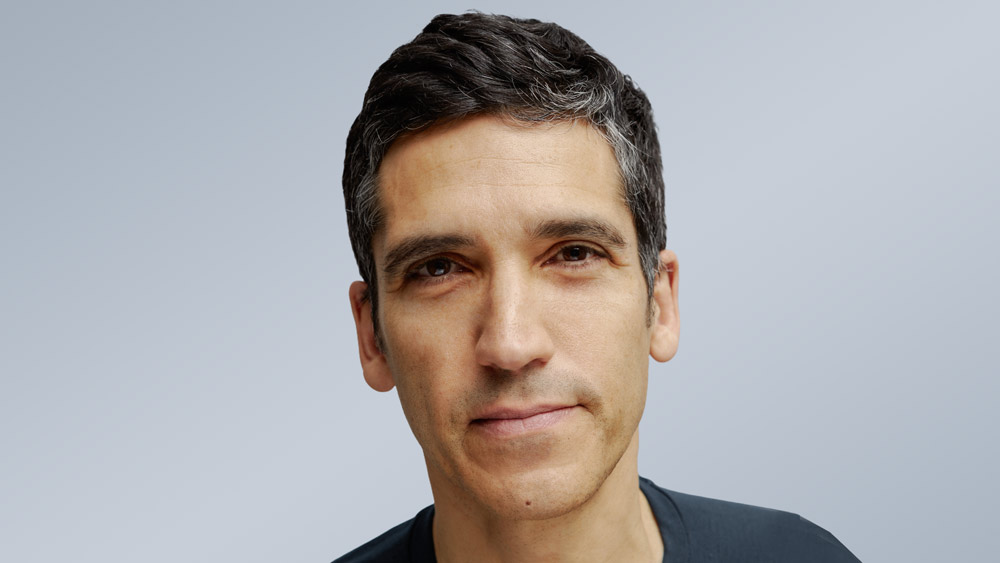

Source: Dean Dalmacio

EDGE: My understanding is you wrote this play after the 2016 elections made you feel that America was slipping into a kind of cultural dementia or senescence. Is that even more the case now in 2024?

Steven Drukman: Did I say senescence or amnesia?

EDGE: I don't recall.

[Laughter]

Steven Drukman: You're right, it was Trump's first victory. And I thought, "Have we just completely forgotten what Matthew Arnold called the definition of culture, which is the best things that have been thought and said in this country?" It seems that we have, and now we're truly in a state of amnesia. We are so forgetful as a nation that we we'll hearken back to the days of "stability," of the "stable genius" of Donald Trump. So, yes, things are absolutely worse.

I used to write for the New York Times, and I interviewed a woman named Diana Trilling, who is a leading female public intellectual. There was something about that interview that made me want to write a play about a Susan Sontag or an Elizabeth Hardwick or a Mary McCarthy, someone like that, and that was in the back of my mind when Trump was elected. I thought, "How would this woman react?" And I thought, "Let's put that sense of cultural amnesia into her head."

EDGE: It's interesting you set the play so far in the past.

Steven Drukman: I put the play in 1988 on purpose, because that was a time when I first experienced this slippage, this moving away from experiencing things in a real sense and favoring a mediated experience. I remember the 1988 election very clearly, [when the candidates for vice president were] Dan Quayle and Lloyd Bentsen. In their debate, Bentsen said, "You're no John Kennedy," and Ted Koppel asked Peter Jennings, who was one of the moderators, "Who do you think won the debate?" Peter Jennings flipped it on him and said, "I'd rather hear who you think won the debate, because you watched it on television" – as if that was more real than being in the same room. I thought, "That's a paradigm shift. We are in a new world now." I wanted to somehow speak to that experience at that time.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.